Consider for a moment your knowledge in different maths topics. Take three, such as algebra, geometry and statistics. Chances are, your skills and knowledge across these topics are not equivalent. In one topic you may excel. Maybe you really like it, or it was taught in a way that resonated strongly, or you play a lot of card games and you happened to pick up some relevant skills along the way.

Then there’s the topic that you struggle with most. You might have been sick and missed a couple of crucial lessons, or you just didn't get the methods that were taught and the topic became about guesswork not understanding.

The point is, you don’t have just one level of understanding across the entirety of maths topics. Your capabilities vary.

Now if we take a whole class of students, not only are there these differences within each student, but we also have differences across students. There is well-established research (see Siemon, Virgona & Corneille 2001, p.37) that in a given Year 7 class, the spread of capabilities is approximately seven years.

Put together, this adds up to enormous variability in student skills and knowledge on any given topic in the classroom.

Bad curriculum advice

Yet your typical Year 7 student, as many state and national curriculum documents would like to have you think, is ready to learn Year 7 level content in all areas of maths (as they are in science, English, history, etc.). Nationally, teachers are instructed to: "refer to the Australian Curriculum learning area content that aligns with their students’ chronological age as the starting point in planning teaching and learning programs." Given all that variability in the classroom, talk about an inefficient approach.

This would be like walking into a shoe store and being told by the salesperson: “Because you’re 25 years-old, here’s a size 8 shoe for you.” What if the shoe doesn’t fit? Of course there’s some acceptance of deviation. “Although size 8 is what people your age typically wear”, the salesperson goes on to say, “Sizes 7.5 and 8.5 are also options because obviously everyone is not the same size.”

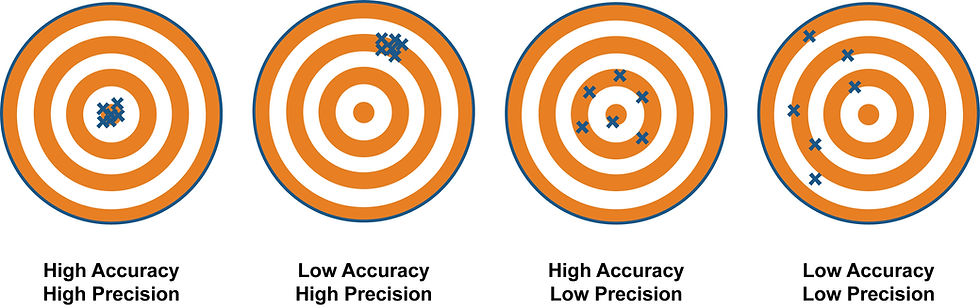

Precision ≠ Accuracy

Our constrained shoe store, like curriculum writers, is confused. Giving every 25 year-old size 8 shoes or every 12 year-old Year 7 level curriculum content is highly precise, but not accurate.

As actuarial and decision scientist Douglas D. Hubbard explains, "'Precision' refers to the reproducibility and conformity of measurements, while 'accuracy' refers to how close a measurement is to its 'true' value." When it comes to the ‘true’ value for each person’s shoe size and for their curriculum knowledge, age is not a helpful place to start. Going to the data and taking measurements is far better and, in maths class, this means diagnostically assessing where each student is at.

The confusion between precision and accuracy, however, is not limited to curriculum writers and mythical shoe stores. Many test developers too, seem unaware of this distinction. You may hope that tests provide objectivity and highlight the patchwork of gaps and competencies that each student has. Instead, there are some completely useless tools that will try to trick you by presenting well-designed questions and glossy data reports, but serve up the same 40 or so questions to each student in a class around a narrow range of content levels. The bell-curve range of questions will mean that the test won't be sensitive to any student not operating around the age-level expectations.

Don’t use these tests if you want an accurate picture of students’ spread of capabilities or to be able to use this data to inform impactful teaching.

Assume diversity

A better approach is one that starts with the assumption that students won’t be the same. A better approach recognises that requiring students to conform and step into ill-fitting shoes is not helpful for them right now or for their long-term development. And instead, it is education-providers (i.e. adults who are in some way involved in the provision of education) who have responsibility for identifying and responding to the diversity within each classroom.

Related post:

Comentários